- The Healthcare Syndicate

- Posts

- Wait and See: Just what the doctor ordered?

Wait and See: Just what the doctor ordered?

When clinical best practices aren’t what the patients want

Introduction

Healthcare costs are exploding, and everyone is arguing about the factors that influence increasing costs.

One factor that isn’t talked as much about is stakeholder preference. To illustrate this point, here’s a harrowing story you might not often hear in the conversation about clinical practice, relayed from a neurosurgeon family friend in Taiwan:

A tattooed, rough-looking 50-year-old man with known ties to the Taiwanese mafia walks into my office for a consultation on his son’s neurological condition. Despite my best efforts to convince him that surgery isn’t the best option for his stage of disease, and his son should explore non-invasive treatment first, the man stood up, got really close to my face, and said, “Are you going to operate on my son or not?” in the most threatening way possible. Fortunately, my staff and I were able to talk him down at the time, but what do you do when patients want treatment that you don’t want to give them?

Doctors are caught between doing what they believe is clinically sound and what patients expect. When patient preference comes into play, the drive to lower cost becomes even more complicated, no matter in a fee-for-service or Value-Based Care model.

Why is customer choice a bigger problem than it seems? For this we found Dr. William Kurtz’s excellent article on the challenges of meeting patient expectations in VBC as a great guide to examine this problem further.

Patients Play a Role in Driving Inappropriate Care:

We’d like to think that patients always follow the expert guidance of their doctors, but the reality is more complicated. In many cases, patients come in with preconceived notions about the type of treatment they need.

They may have done their own research, often online, or talked to friends and family who’ve had similar issues. This can lead them to push for treatments that may not be appropriate for their specific condition, and they may resist more conservative approaches, like physical therapy or lifestyle changes, that are often recommended first.

When patients push for more invasive or unnecessary treatments, it not only drives up costs but also complicates efforts to move toward value-based care (VBC) models, which are designed to optimize both quality and cost efficiency. As long as patients believe that “more” treatment means “better” care, we’ll struggle to change the dynamic.

The “Caring” Physician Dilemma

Physicians, too, are caught in a difficult position. Patients often perceive doctors who over-treat as more caring and thorough compared to those who recommend less intervention. “Caring” doctors will likely see more business as positive word of mouth increases likelihood of getting referrals.

This presents a significant barrier for VBC, where the goal is to reduce unnecessary care while improving outcomes. If patients view reduced intervention as reduced quality, then the financial incentives in VBC are undermined by a cultural and emotional disconnect between patients and physician.

Financial incentives clash with the human aspect of care:

In an effort to stamp out the rising cost of healthcare, value-based care (VBC) has been touted as a solution to control spending, typically through a fixed payment model for a disease state. While specifics may vary, this model essentially caps how much healthcare organizations can spend on a particular condition per patient, ensuring that care is provided within an agreed-upon budget.

However, what we tend to overlook is that profitability remains the driving force for all for-profit healthcare organizations, just as it does for any other industry. While one can debate the morality of a profit-driven approach in healthcare, it has undeniably fueled innovation, efficiency, and resource allocation strategies that allow organizations to thrive in a competitive marketplace. The pressure to stay profitable pushes organizations to improve operations and find ways to meet demand, albeit with potential downsides when profit takes priority over patient outcomes.

I do agree that the fee-for-service (FFS) model, which pays providers based on the number of services they deliver, can be abused and should be gradually phased out. However, it does have certain benefits. One of these is the flexibility it provides physicians to step outside the rigid clinical playbook from time to time. They can offer additional care or tests to meet the demands of patients without worrying about the financial repercussions on the organization. This model also allows healthcare organizations to generate additional revenue through increased services, which can, in some cases, improve patient satisfaction.

But since providing more services don’t directly lead to higher revenues in VBC arrangements, this can lead organizations to the other most straightforward solution: cutting costs. This is where we run into conflict—what the patient wants vs. what clinical guidelines suggest is most beneficial at the lowest cost. In many cases, the patient’s expectations of “quality care” involve more intervention, not less, which directly contradicts the cost-saving objectives of VBC.

The healthcare business is notoriously difficult because of the number of stakeholders trying to accomplish the same goal of improving patient health from different perspectives.

In light of this unique dynamic, what should we do to solve this dilemma, specifically around preference and customer choice?

Focus on Patient Education

The key lesson here is to anchor the patient to the clinically appropriate course of treatment before they develop other expectations.

This means educating patients as soon as possible about the realistic benefits and risks of different treatment paths, so they’re less likely to demand unnecessary or inappropriate care later. Startups that build systems or tools to reinforce patient education at the earliest stage of the care process can create a smoother path for both patient satisfaction and cost-effective care delivery.

For example, Dr. William Kurtz's article suggests:

Providing written information about conservative care is often better received by patients than a verbal lecture about why the patient’s request for an immediate MRI is unwarranted. When I discuss conservative care with a patient, it can feel like I am attacking their preconceived aggressive treatment plan, which is personal. When I give a patient written information with clinical references to studies that support conservative care, it is more objective because the written educational material was produced for a general audience and not a personal attack.

Match the patient to the right type of doctor

Patients choices aren’t the only factors at play. The “At Least Once” rule provides a statistical framework to understand just how much physician preference can also increase the chances of inappropriate care. The rule calculates the probability that a patient will find a doctor who agrees with their desired aggressive treatment plan after seeking multiple opinions.

Again from the article:

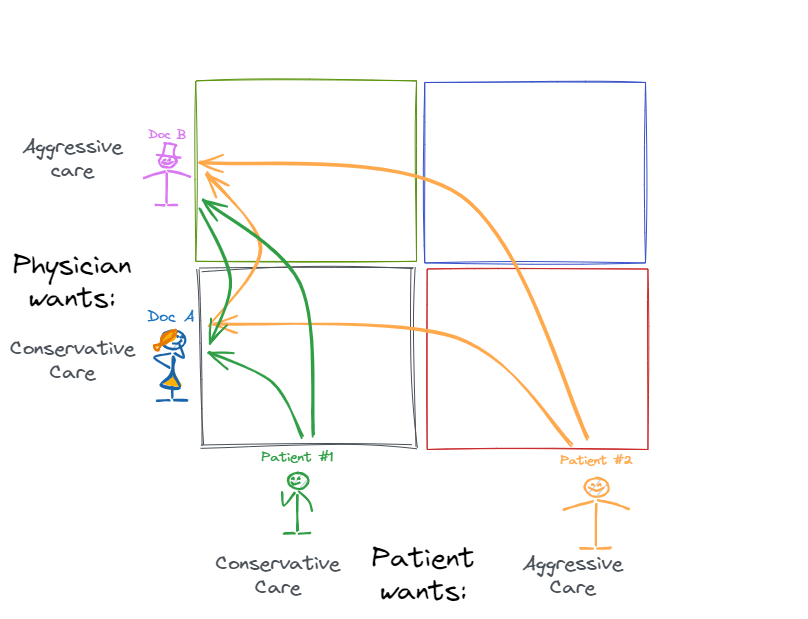

Let’s assume Doc A is conservative and recommends aggressive care 10% of the time. Doc A is low on the Y axis. Doc B is aggressive, recommends aggressive care 80% of the time, and is high on the Y axis. Patient 1 prefers conservative care and is low on the X axis. Patient 2 prefers aggressive care and is high on the X axis. For this example, we will assume that if the doctor recommends a treatment that the patient does not want, then the patient will seek a second opinion. We will also assume that Patient 1 and Patient 2 have the same MSK problem that could be properly treated conservatively or aggressively.

When Patient 1 sees both doctors, the likelihood of getting the conservative care they want is 1 minus (0.1x0.8) = 92%. When Patient 2 sees the same two doctors, the likelihood of getting the aggressive care they want is 1 minus (0.9x0.2) = 82%.

This statistical insight demonstrates why physician tendencies is just as important a factor to manage. A patient with a preconceived notion of aggressive care will be more likely to find a doctor who aligns with their preferences if they keep seeking additional opinions. In fact, the statistical likelihood of getting the treatment they desire increases with each new doctor they see. This is why understanding physician tendencies is crucial—knowing how likely a physician is to recommend aggressive care can be an important part of steering patients toward appropriate, evidence-based care.

It is important to note though that not all aggressive care is inappropriate. From Dr Kurtz:

Despite trying to steer the patient towards conservative care, I would rather order an unnecessary MRI than have the patient seek care from an aggressive physician. At least, I might have the opportunity to discuss the MRI findings and prevent an unnecessary surgery.

Beyond serious cases that requires urgent intervention, patient satisfaction is also a key area for healthcare organization reimbursement, so skillfully meeting patient expectations by allowing for more aggressive options occasionally isn’t the end of the world.

Conclusion

The complexity of the healthcare business stems not only from the medical challenges but also from the varied preferences and expectations of its stakeholders—patients, physicians, and healthcare organizations. Patients, empowered by their own research and experiences, often push for treatments that may not align with evidence-based recommendations. On the other side, physicians differ in their treatment preferences, with some favoring conservative care and others leaning toward aggressive interventions. These mismatched expectations add layers of complexity to healthcare delivery.

In the end, healthcare is about finding that balance between meeting patient needs, controlling costs, and ensuring that care remains both high-quality and evidence-driven. By understanding and managing the different preferences of both patients and physicians, healthcare organizations can improve outcomes and lower costs without sacrificing patient satisfaction. This will require ongoing efforts in education, the use of data-driven tools, and careful matching of patients with physicians whose treatment philosophy aligns with best practices.

Please subscribe to our newsletter if you haven’t, and share our newsletter with a friend. Stay tuned to our newsletter for more insights into healthcare innovation!

Join us at The Healthcare Syndicate as we back the most ambitious founders 10Xing the standard of healthcare!

Reply